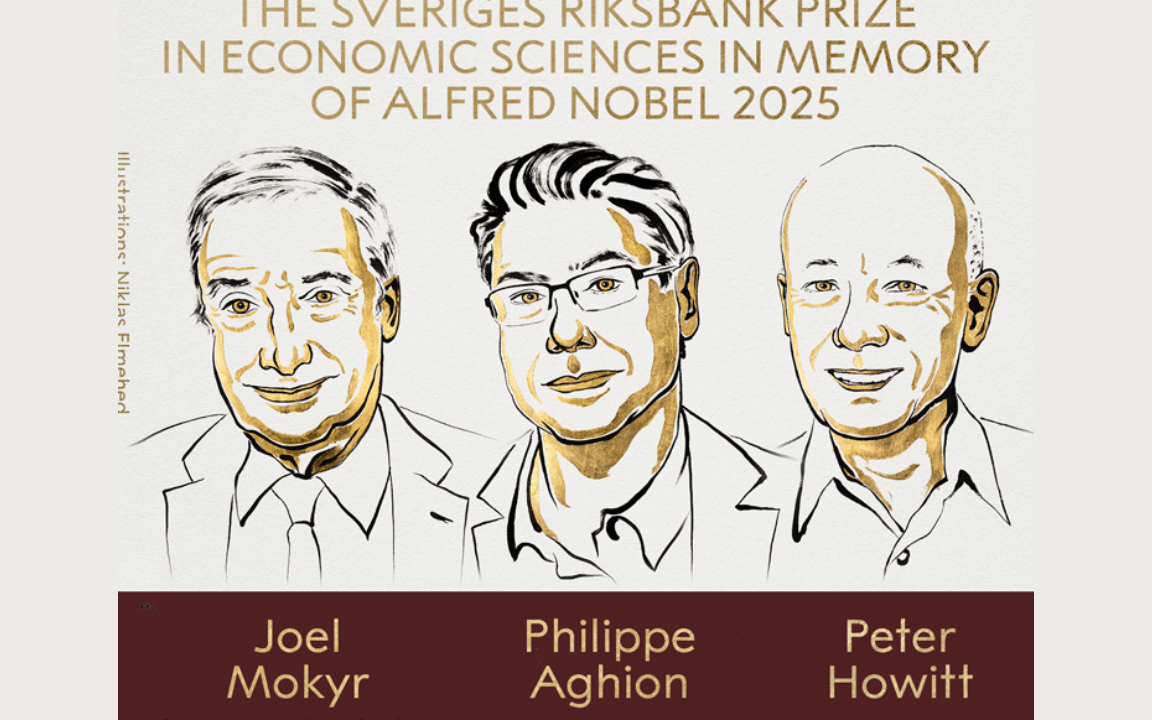

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences did more than celebrate three brilliant thinkers. It was a subtle alarm bell about how innovation happens, why it slows down, and what societies lose when they stop believing in progress.

Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt were the joint winners, and they all come from very different corners of economics. Together they explained both how the modern world began to grow, and what keeps it from stalling.

Their ideas tell a single story about innovation, competition, and the fragile culture that allows growth to last.

How growth became possible

For almost all of human history, economies barely moved. Small improvements in tools or farming were erased by population growth and war. Joel Mokyr, the economic historian at Northwestern University, has spent a lifetime asking why the Industrial Revolution broke this pattern. His answer is not coal or conquest, but ideas.

Mokyr’s research shows that eighteenth-century Britain created a unique loop between science and practice. Scientists discovered why things worked. Craftsmen and engineers figured out how to make them work better. Knowledge became cumulative.

This connection between “heads and hands,” as Mokyr calls it, produced the first sustained rise in living standards in history.

He calls this period an “Industrial Enlightenment.” Scientific societies, printing presses, and a culture of open debate let information spread faster than ever. Skilled artisans, which are the “upper-tail human capital” between elite scientists and ordinary workers, were the bridge.

They could read, tinker, and turn theory into machinery. It was not wealth or empire that made Britain different but a culture that accepted trial, error, and disruption. Mokyr’s point is simple and unsettling: progress is rare, and it can stop if that culture fades.

The engine that keeps growth alive

Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt explained what happens after the takeoff. Their theory, known as Schumpeterian growth, describes how economies keep advancing once innovation starts.

In their 1992 paper A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction, they showed that new technologies do not simply add to old ones. They replace them.

In their model, each innovation destroys part of the old economy. Firms invest in research to become temporary leaders, knowing that the next discovery will soon make them obsolete. Growth is not smooth. It depends on a constant turnover of firms and ideas.

That process is called creative destruction, and it drives both productivity and pain. Workers lose jobs. Old industries vanish. Yet without this churn, growth stops.

Later work by Aghion and his co-authors found that the relationship between competition and innovation follows an inverted U-shape. When markets are too concentrated, firms feel no threat and stop innovating. When competition is cut-throat, profits disappear and research slows.

Innovation ultimately peaks when companies are “neck and neck,” racing for temporary dominance. That idea now guides how economists think about regulation, antitrust, and industrial policy.

Empirical studies have backed much of this theory. Data on firm entry and exit from the United States, the UK, and Eastern Europe show that productivity grows fastest when resources shift from old firms to new ones.

This reallocation is how creative destruction looks in the real world.

Innovation is never automatic

The Nobel committee framed the 2025 prize as a story about how technological progress sustains prosperity. And the message is timely.

Across the West, productivity growth has slowed, while skepticism toward technology and global trade has grown. Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt offer a reminder that innovation is not a natural state. It depends on competition, openness, and faith in progress.

Reallocation is extremely important. Economic growth is not just the discovery of new ideas but the ability of an economy to move people and capital toward those who can use them.

The United States tends to do this better than Europe because its labor and product markets are more flexible. In fact, a $11 trillion gap has been created between the US and Europe over the past 17 years.

Yet even there, business dynamism has declined for two decades. The risk is that societies keep inventing but lose the capacity to adapt.

Kevin Bryan, one of Mokyr’s former students, sees the prize as the culmination of seventy years of work on growth. From Solow’s 1957 discovery that most growth came from a mysterious “residual,” to modern endogenous growth theory, economists have been trying to explain what that residual really is.

For Aghion and Howitt, it is competition and incentives. For Mokyr, it is culture and knowledge. The combination is what sustains prosperity.

Why the committee’s choice matters now

Not everyone in the field agreed with the decision, as Mokyr’s cultural explanations are hard to test. They break from the recent trend of Nobel prizes rewarding data-heavy, empirical work. The committee may have been making a statement beyond academia.

Across the United States and Europe, public attitudes toward progress have darkened. Some call for “degrowth.” Others fear artificial intelligence or reject new technologies outright.

The Nobel is a reminder that the West’s rise was built on confidence in science and invention. Losing that faith could be as damaging as any policy mistake.

Anton Howes, a historian who has worked closely with Mokyr, sees the award as a victory for economic history itself. In a profession dominated by regression tables and identification strategies, Mokyr’s success proves that narrative work can still change minds.

His books are written for readers outside academia but grounded in economic logic. They make the history of ideas readable again.

The lesson behind the medal

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics was not just about past theories, but about the conditions that make future growth possible.

Mokyr showed how societies once learned to believe in progress. Aghion and Howitt showed what keeps that belief productive. Together they describe a system that is powerful, albeit fragile.

When competition fades, when knowledge is hoarded, when societies fear change, the “culture of growth” weakens. The world that began in the workshops of eighteenth-century Britain did not arise by chance. It was built on a set of ideas that must be renewed every generation.

The Nobel committee’s message could not be clearer: progress is not guaranteed, and believing in it may be the most important innovation of all.

The post Why the 2025 Nobel prize in economics is a warning about the future of progress appeared first on Invezz